Texas Surgeon Goes Baroque with Gift to BYU School of Music

May 2014

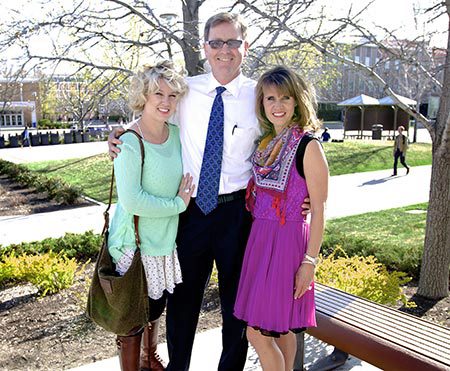

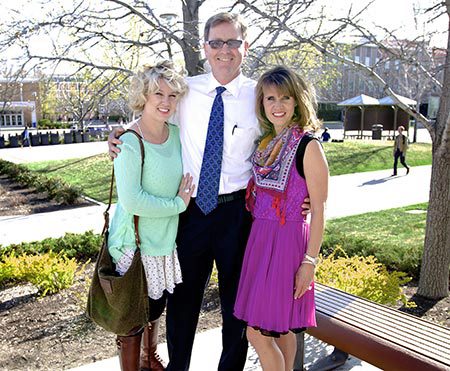

Scott Smith watched students come and go from the Harris Fine Arts Center during his years at BYU and sometimes wondered what those students with instrument cases slung over their shoulders ever expected to accomplish with their fine arts degrees.

Little did he know that in a few short years, he would have a son at BYU carrying one of those imposing instrument cases, and, as a result, he would be making a sizeable gift to the School of Music.

Scott came from an athletic family. His brothers excelled in BYU sports - including, among other highlights, a key touchdown catch during the famed 1984 football championship season - so the field of fine arts was uncharted territory in his experience.

He thrived on the sciences and earned a chemical engineering degree on his way to medical school. He is now a surgeon in Granbury, Texas, where he specializes in back surgery and designs medical equipment.

His wife, Sheila, whom he met at BYU, was equally enveloped in her business finance degree.

After they got married, it was something of an eye-opener when their seven children came along. One by one, each discovered his or her talent in fields very different from Scott’s or Sheila’s - beginning with the first child, Jeffrey, who has now graduated from BYU and is a master’s degree candidate in violin performance at New York University.

“Each child is made from scratch,” Scott said. “There is nothing store-bought or mass-produced about their personalities.”

“Each has his or her own cute chocolate chips,” said Sheila, explaining that it’s the special things that go into chocolate chips like the raisins and nuts that makes each cookie unique.

Over the years, the Smiths have provided myriad opportunities for their children to find their talents by exposing them to many experiences. They provided a safe setting where each could sample from a smorgasbord of activities.Jeffrey, for instance, showed little promise as a musician when he started playing the cello at age eight. “It seemed like lunacy when Jeffrey picked up the violin several years later,” Scott said. “He was the worst in the class. It was no surprise when the teacher offered personalized help. But in six months, when the wiring connected, Jeffrey zoomed from worst to the best.”

Where once he played “Arkansas Traveler” in the family dining room, now he is concertmaster in the university orchestra, having come a long, accelerated way from the time when he played as a young teen with his sister Karlee in the Midland/Odessa professional orchestra in his crooked bow tie.

In that same spirit of helping their children flourish, the Smiths were eager to donate to the School of Music when the opportunity was presented to them to purchase authentically crafted Baroque string instruments.

Because of their gift, the School of Music was able to purchase six violins, three violas, and two cellos that were built in the same way as instruments of the Baroque era, approximately 1600–1750. These new additions provide students with the look, feel, and sound of the instruments that Bach or Vivaldi would have known.

“This is not about a name on a plaque,” said Scott. “This is about making something exciting happen, helping students discover their passion. It’s about creating beauty.”

“We want to put something into their hands that will improve their abilities,” said Sheila. “There is satisfaction in this kind of gift. Who doesn’t love this music? It’s fun. It’s toe tapping. We love giving gifts that will bless our children, and then their children and others along the way.”

“Many universities have early music ensembles,” said BYU School of Music director Kory Katseanes, “but very, very few have their own authentically crafted Baroque instrument collection. This experience sets our students apart from other music students and gives them an artistic and educational advantage.”

And every advantage can help as music school graduates seek to set themselves apart from others, Scott said.

Comparing his experience of entering medical school with his son’s experience of entering music school, Scott said, “The competition to enter medical school doesn’t compare with the competition to enter a program like Juilliard or Curtis. Entering music school is much more fierce.”

After receiving the Smiths’ donation, the School of Music approached the Violin Making School of America in Salt Lake City to create these specialized instruments. The school was founded in 1972 by German artisan Peter Prier, who learned his violin-making skills from old-world masters. Stepping into the school is like stepping into Italy at the time of Stradivari.

Today’s violins differ in many ways from the ones created in the 1700s, beginning with steel strings replacing the old ones made of sheep intestines. There are also differences in the fingerboard, neck, bridge, and bass bar. In the 1700s, cellos didn’t have endpins and were held between pinched knees. Bows were also different and contribute to the authentic sound of the period’s instruments.

Charles Woolf and Sanghoon Lee, principal directors at the Violin Making School, studied extensively to create instruments reminiscent of the Baroque era.

“There was no one document or picture that showed how instruments looked in those days,” Charles said. Learning to build a Baroque instrument required piecing together many tidbits of scattered information and filling in the blanks where nothing existed.

They began by taking new instruments that were hanging on the wall and prying off the tops - a process that is painstakingly slow and requires calm nerves, he continued.

Taking the top off of a new violin reduced more than one student to tears, Sanghoon said.

“The project was quite challenging,” added Charles. “In fact, it was a headache. We had to deal with many problems. It took lots of encouragement to keep students going, but in the end it was very satisfying.”

Charles compared the process to fitting a modern car with wagon wheels. Tires and wagon wheels are both round, but they aren’t interchangeable.

After much dedication and hard work from the violin-making experts, the School of Music received the instruments and put them to use in its Baroque Ensemble.

“The BYU Baroque Ensemble is the nexus of four unique entities,” said Katseanes. “It brings together the musicality of our BYU music majors and faculty, the creativity of students and faculty of the Violin Making School of America, the genius of great composers, and the generosity of Scott and Sheila Smith. It took all four.”

“This is the kind of partnership that really defines the arts - craftsmen, composers, performers, and patrons. This is the ‘village’ it takes to raise artists. I’m especially grateful that we have parents and families like the Smiths, who, in addition to sending their talented children to BYU, also are willing to help us raise the bar of educational opportunities. The School of Music is a richer, more comprehensive, more creative environment now. We are more than competitive; we’re at the front of innovation and educational opportunity.”

You Can Help

The BYU Baroque Ensemble is not your typical, cookie-cutter musical group. This is a unique chocolate chip. It came about because of a professor’s desire to give students specialized musical training, coupled with two donors’ desire to give a gift that would bless their posterity.

As a result, BYU students will prosper. They will enter the world of music with a distinctive competitive advantage.

Have you considered how you might share your passion with others by giving a gift to BYU? Imagine how your gift - as in the case of the Baroque Ensemble instruments - could be displayed around the world.

Make a Gift