Searching for a Cure in Russian

After learning about her family history of cancer, Emily Hoskins knew that she wanted to use her Russian and bioinformatics skills to find a cure.

December 2014

Source: BYU News

Editor’s note: Mentored learning programs at BYU are funded by donors. We are grateful to those who financially support talented BYU students as they prepare to make significant contributions to the world.

No matter what type of chemotherapy you attack a tumor with, many cancer cells resort to the same survival tactic: They start eating themselves.

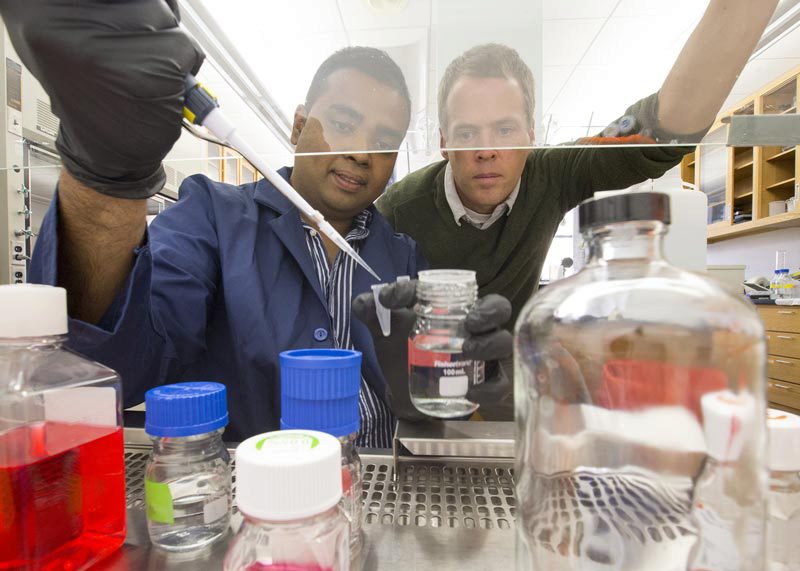

Scientists at Brigham Young University discovered the two proteins that pair up and switch on this process – known as autophagy.

“This gives us a therapeutic avenue to target autophagy in tumors,” said Josh Andersen, a BYU chemistry professor. “The idea would be to make tumors more chemo-sensitive. You could target these proteins and the mechanism of this switch to block autophagy, which would allow for lower doses of chemotherapy while hopefully improving patient outcomes.”

Weerasekara directed the lab experiments and co-authored the study.

Weerasekara directed the lab experiments and co-authored the study.Lower doses would mean milder side effects. The prospect spurred an international hunt for this switch. For good reason, several other labs started with a protein called ATG9 as their prime suspect and then looked for its accomplice among thousands of other proteins.

But the BYU team, comprised mainly of undergraduate students, stumbled into the race unexpectedly, coming at it from a different direction. They wanted to know why cancer cells made a surplus of protein called 14-3-3 zeta.

Using breast cancer tissue in the lab, they forced tumor cells to undergo autophagy by depriving them of oxygen and glucose. A comparison with a control group let them see that the two proteins hook up only when under attack. That’s because stress makes Atg9 undergo a modification that enables 14-3-3 zeta to bind with it and switch the cancer cells to survival mode. (Read more at BYU News)

After learning about her family history of cancer, Emily Hoskins knew that she wanted to use her Russian and bioinformatics skills to find a cure.

Jenny Pattison’s story came full circle from what started with her dad getting cancer, to her fellowship at the BYU Simmons Center for Cancer Research. She has found a way to turn her tragedy into something that could someday bless other families like hers.

Marco Crosland took the top spot this year - and last year - at the National Collegiate Landscape Competition. He is a landscape management student and a grateful beneficiary of your support.