Finding the Loves of His Life in Laie

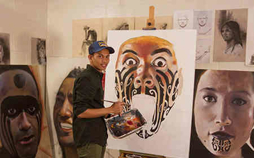

Nelson, a BYU–Hawaii IWORK student from Tahiti who works at the Polynesian Cultural Center, says he found the two loves of his life in Laie: his passion for art and graphic design and his wife, Rahei.

June 2016

When Sery Kone was four years old, his parents divorced, and his dad took him from his mom, abandoned him in a village 1,200 miles away, and never came back. Sery found himself working on an Ivory Coast cacao farm as a child slave, laboring 10 hours a day just to get enough food to survive.

“When I was eight years old, I remember working with a younger boy who was extremely tired,” Sery says. “I told him to rest and I would finish his work. The owner of the farm started yelling at us. I said, ‘I told him not to work, and I will do his job.’ The owner beat us both. I thought, ‘Why? Why do I have to be here now while other children have good lives? Why are we here working hard and getting beaten?’ I promised myself that I would figure a way out but come back later to help.”

Sery spent six long years on the cacao farm before he dared to leave and find his way back home. With no money, he boarded a bus for the city of his birth. The driver was about to kick him off when a stranger paid the fare - the first act of charity Sery had ever received. After sleeping on the streets for two weeks, he made his way to an orphanage, where he decided to take charge of his life. “I went to the marketplace every morning and offered to carry baskets,” he says. “Women would give me 20 or 30 cents. It was difficult but I was happy. I made enough money to buy the food I wanted.”

After a few months Sery found his family, only to discover that his mother had died from the grief of losing him, her only child. “I was angry,” he says. “I started to question everything. If there was a God, why would He let this happen to me? I had done nothing wrong.”

Because he was angry with God, Sery refused to go to church with his grandmother. Instead, he stayed home and argued with passing street preachers. When he was 15 years old he met two “street preachers” who were different - missionaries from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

“I read the story of Joseph Smith,” Sery says. “I didn’t get a powerful spiritual testimony at the time, but it made sense to me. I felt connected to this 14-year-old boy. He was poor; I was poor. He was trying to find his way; I was trying to find my way.”

Sery opened up to the missionaries about his past and the pain he felt. He learned about the plan of salvation, and the Holy Ghost bore witness to him that it was true. “It changed my life,” he says. “I was baptized two weeks later.”

For the next five years he studied diligently in school. As he prepared for the college entrance exam, he prayed for help. He says, “I made a promise to God: ‘If I pass, I’ll go on a mission.’ I passed, so I knew I had to fulfill my promise.” University officials told him that if he served a mission he would be banned from coming back to school. Sery chose to serve the Lord.

Thanks to assistance from the Church’s General Missionary Fund, Sery served a full-time mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. “I still carried anger from my childhood hardships,” he says, but while serving in the poverty-stricken area of Kinshasa, “my attitude changed when I saw others in desperate situations. I realized my blessings and stopped mourning the challenges I had gone through.”

Sery could not resist helping people in serious need. Sometimes he spent his own mission stipend on others. Near the end of his mission, he was transferred to an area where only five members regularly attended church. “By the time I left my mission,” he says, “ we had a branch of 150 newly baptized members. The Lord helped me know where to go and what to say by the Spirit.”

In 2009 Sery returned home from his mission and applied to several universities, but, true to the warning he had received, he was not accepted. He emailed his former mission president, who agreed to help him get into a Church school if he could learn English and save $6,000. After years of hard work, Sery and was admitted to BYU-Hawaii.

Despite his efforts and savings, Sery could not afford to attend BYU-Hawaii without the university’s donor-funded financial aid programs. “The scholarship system offered the opportunity for me to get an education,” Sery says. “Without that it would have been extremely difficult for me to go through school and finish my degree.”

As soon as Sery got to BYU-Hawaii, he started to research child slavery in the chocolate industry. He thought, “What is the bigger picture here? Not all farmers are bad people. They are our brothers, our sisters, and our friends. How can we help everyone be part of the solution?”

Sery’s drive to find solutions led him to join BYU-Hawaii’s student-run chapter of Enactus - an international non-profit organization that mobilizes university students to make a difference in their communities and acquire the skills to become socially responsible business leaders. He developed a plan to help fight child slavery, entered it in BYU-Hawaii’s Great Ideas competition, and won second place. He sent the $300 prize money home to the Ivory Coast to buy Christmas presents for 70 impoverished children.

To put his plan into action, Sery founded a non-profit initiative called WELL Africa (WELL stands for World Education for a Legacy of Liberty) to build schools for children who work on cacao farms. “I wanted to show farmers how helping children attend school could profit them and help the children succeed,” he says. He entered another BYU-Hawaii competition, Empower Your Dreams, and won the first-place award of $5,000. He used $3,000 to fly to Africa to move his plan forward.

On his first visit home, Sery fought back tears as he saw young children working on farms. He felt deeply the pain of their unrealized dreams, and his determination grew.

“I scheduled appointments with high-ranking government officials, teachers, farmers, villagers, and community leaders,” he says. “I told them my story and how I wanted to help. They liked that I was not blaming anybody but rather trying to bring people together to solve problems.”

Sery explains, “Nobody was guilty, but everybody was responsible. The farmers wanted to increase their profit, so they looked for the cheapest workers available - the children. Our plan was to build schools next to farmlands so kids could go to school half day and work half day.

“We suggested new agricultural techniques to make the process more efficient and profitable for farmers. We proposed that they keep 80 percent of the production for themselves and give us 20 percent to feed the children attending school. So far it’s worked really well.”

When the national government wanted to help, Sery asked if they would provide teachers and let them teach the gospel in school. They said yes, and they gave the schools full control over the curriculum.

A major BYU-Hawaii donor stepped up to financially support Sery’s initiative, and in September 2014, the first school opened its doors to 300 students in the Ivory Coast. Sery put together a small team in Africa to maintain progress while he finished his education.

Other students from BYU-Hawaii’s Enactus chapter rallied around Sery to help make his dream a reality. “I’ve surrounded myself with those who have the expertise I need,” he says. “I express needs, people come up with ways and budget, and we find resources.” In 2015 their team won first place in the national Enactus competition. They went to South Africa to compete in the Enactus World Cup, where they came in second place in the entire world.

Sery’s efforts are already bearing fruit. “The first time I returned to a village,” he says, “I saw children with machetes working in the cacao farms. Now I see children with books, pens, pencils, and bags going to the school we built. I see farmers working unpaid to help and even providing construction materials. That is hard to believe.”

Sery graduated from BYU-Hawaii in April 2015 and currently works on the global audit team of a major U.S. corporation. He plans to earn an MBA at BYU and continue building schools in Africa to give the children the hope he so desperately desired. “They now see possibility,” he says. “Children can make life better for themselves, their families, and their communities.”

Today Sery views his hardships as helpful preparation. “I have depended on others for housing, food, education, and the gospel,” he says. “Today the Lord is helping me provide education for children in Africa. If I open my heart and mind, the Lord gives me and others what we need.”

Sery continues, “None of the things that happened at BYU-Hawaii would have been possible without the help of the students, the faculty members, and members of the administration here. I think the school is really true to its mission, which is to learn, to lead, and to become leaders. I truly got those opportunities. I learned, and now I’m given opportunities to lead.”

Nelson, a BYU–Hawaii IWORK student from Tahiti who works at the Polynesian Cultural Center, says he found the two loves of his life in Laie: his passion for art and graphic design and his wife, Rahei.

RJ, a BYU-Hawaii IWORK student from the Philippines, went from imitating artwork from Church magazines to studying art in Paris and New York thanks to scholarships and internships.

Kazu, a BYU-Hawaii student from Japan, struggled to learn English as a high school student. His desire to attend BYU–Hawaii motivated him to study hard, and he finished in the top of his class. Now he is enjoying opportunities he didn’t imagine were possible.